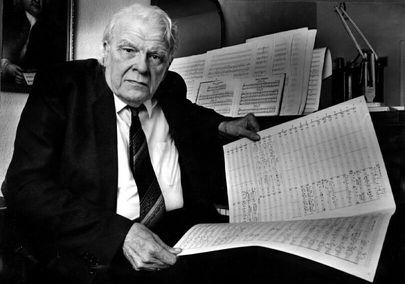

20th Century Organists: Part I Philip Marshall

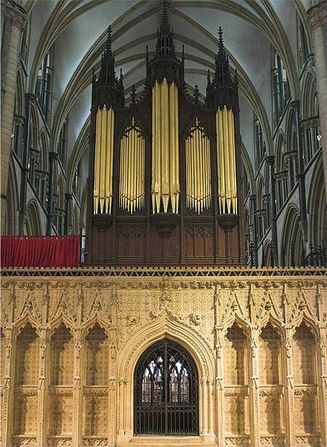

Hearing the Psalms of David sung to Anglican chants is not always a rich musical experience. For many years, Philip Marshall, first at Ripon Cathedral (1957-1966), then at Lincoln Cathedral until 1986 showed that this could be a very highly developed art form. (At the same time David Willcocks, at King's, Cambridge, was similarly engaged.)

Philip's accompaniments always made the psalms interesting, sometimes thrilling. Despite their usually being sung in four-part harmony, no two verses of any chant seemed to have the same accompaniment. Inversions, variations and counter-melodies - at Lincoln often on Willis's haunting orchestral oboe - appeared with unending fluency. Haydn's orchestration in The Creation came to mind as valleys, thick with corn, laughed and sang (Psalm 65), a singularly fierce-sounding lion growled for prey (17) or axes and hammers were heard at their fell work (74). These were not sound-effects, but essential parts of elaborate scores emanating from a seemingly inexhaustible imagination.

|

This same fertility of invention made Philip an outstanding extemporiser; to appreciate this, total concentration was needed on the part of listeners. Even then, those comparing notes usually discovered that each had missed some fine point. A minor amusement was listening for Elgar, from whom some quotation could usually be heard. Sadly, he made few recordings, concentrating his energies on his cathedral, its city and diocese. As lecturer, choirmaster and conductor he was greatly appreciated, despite his north-country bluntness and lack of patience with anything less than total effort.

Trends that developed in worship during the 1960s caused Philip much concern. He loved the liturgy of the Book of Common Prayer and the musical tradition that had been built round it: this was clearly under threat. He was also dismayed at the fashions of the time in organ-building. His views are expressed in the Marshall's Christmas card for 1969. This, set to an ingenious musical score, was individually prepared for each recipient in his flawless calligraphy:- "God rest ye merry organists, let nothing you dismay:

"For though 'pop' services are here, they soon will pass away. "So couple up your heavy reeds and join my cheerful lay." "We're now frustrated organists. "O tracker-lack-a-day! "We've only Scharfs and Larigots to shriek your loathsome lay: "And we CAN'T couple heavy reeds (Ralph Downes has taken them away)." |

This, it should be remembered, was written soon after Ralph Downes' proposals for Gloucester cathedral organ were made known. The diapasons, tuba, orchestral reeds and strings of Father Willis's superb instrument, together with its 32' pedal were removed. The neo-classical organ that replaced it, whatever its qualities, was far less well-adapted to the needs of a cathedral (and over the years, has had some work to remedy some of its shortcomings). Those who know the work of Ernest Skinner in the USA will appreciate the sense of the loss felt by many at the destruction of the Willis.

Lincoln's first sighting of its new organist after his appointment was of Philip in shirt-sleeves with planks of wood and rolls of wire making cat-proof the garden of his house. This was close to a road carrying increasing amounts of traffic; Thomas Tompkins and Nimrod – indeed a mighty hunter – had to be kept safe. Finer craftsmanship was displayed in the chamber organs he built and in various instruments he transferred from old homes to new, often renewing worn action and correcting other faults in the process.Formidable skills were employed in the construction of large-scale working steam locomotives - memory suggests a gauge of about 2 ½ inches. (Engineers will be impressed to know that he honed the cylinders himself.)

Lincoln's first sighting of its new organist after his appointment was of Philip in shirt-sleeves with planks of wood and rolls of wire making cat-proof the garden of his house. This was close to a road carrying increasing amounts of traffic; Thomas Tompkins and Nimrod – indeed a mighty hunter – had to be kept safe. Finer craftsmanship was displayed in the chamber organs he built and in various instruments he transferred from old homes to new, often renewing worn action and correcting other faults in the process.Formidable skills were employed in the construction of large-scale working steam locomotives - memory suggests a gauge of about 2 ½ inches. (Engineers will be impressed to know that he honed the cylinders himself.)

|

Railways and railway travel were important to Philip, who gave the closure of the line serving Ripon as a major factor in his decision to move to Lincoln. (This may have been a joke: you couldn't always tell.) Certainly, he usually seemed to live in a place with good rail connections. Before he moved to Ripon, he was organist of the parish church in Boston, Lincolnshire. Its spire looks down on the harbour whence the Pilgrim fathers sailed in the Mayflower (1620). Unsuccessful attempts to develop this harbour in Victorian times had left it with better rail connections than it might otherwise have had.

Philip Marshall inspired affection, awe and respect – often in equal measure. Those who knew him and his work regret the extreme modesty that kept him from seeking wider audiences. Several of Philip's recordings, originally issued on vinyl, have been transferred to CD and are still available. Next month, we remember a French organist, titulaire of one of the great Paris churches, who was born in the same year as Philip and had much in common with him beside. Anyone care to guess? |

David Bridgeman-Sutton, July, 2009

Words "God Rest ye Merry Organists" : copyright the estate of the late Dr Philip Marshall