Byway ~ The end of Brindley and Foster

Brindley and Foster organs were doomed to disappear ~

David Bridgeman-Sutton follows their demise (Part II)

David Bridgeman-Sutton follows their demise (Part II)

|

The previous page (part 1) mentions an organist who knew a Brindley & Foster instrument soon after it was built. She was delighted by its performance.

Experiences 30 years later were less satisfactory. The same lady said:“It started with occasional ciphers, sometimes on several notes. A choir-member would remove the offending pipes, only for the trouble to begin again somewhere else. A little later the drawstop action and transformers started to misbehave, refusing to come on or to go off, or even doing so entirely of their own accord. In later years, that organ became a nightmare.” This view was shared by organ-builders, many of whom were most reluctant to touch a B&F instrument. |

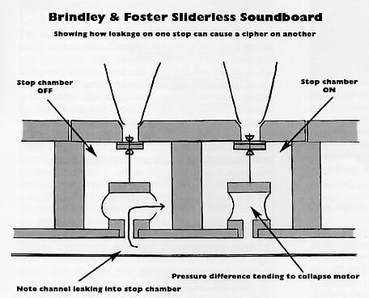

John Norman's diagram (pic 1) shows weaknesses in design that led to trouble in the sliderless windchests employed by the firm. These were necessary to permit the use of “transformers” and other registration aids. Complexities in these movements later caused their own problems, as wear took place. Some organ builders refused to work on B & F instruments, renaming the “metechotic” action “metechaotic”. After the firm had been taken over by Willis, it became virtually impossible to find a builder willing to restore a Brindley organ unless the contract allowed provision of new windchests and action throughout.

An oddity of the firm was a tendency to use large numbers of dummies as facade or case pipes. This could produce curious results. In one case, some mis-measurement resulted in a facade that should have stood clear of an arch failing to do so by about one-and-a-half inches. The remedy was to cut the pipes in the manner of topiary, to fit round the mouldings of the stonework. The result was, to say the least, striking. Elsewhere, front pipes might be omitted altogether, sometimes replaced by curtains.

An oddity of the firm was a tendency to use large numbers of dummies as facade or case pipes. This could produce curious results. In one case, some mis-measurement resulted in a facade that should have stood clear of an arch failing to do so by about one-and-a-half inches. The remedy was to cut the pipes in the manner of topiary, to fit round the mouldings of the stonework. The result was, to say the least, striking. Elsewhere, front pipes might be omitted altogether, sometimes replaced by curtains.

|

Picture 2 shows the excellent architect-designed case of St Anne, Worksop, as Brindley & Foster left it and as it stood for 80 years. The curtained front, reminiscent of the silk panels found in some Victorian parlour-pianos, is decidedly unhappy. Goetze & Gwynne have recently transferred a mid-Victorian instrument into the case, which now looks much happier, be-piped as the designer intended (pic 3). Note also how well the console of the “new” organ fits in.

Many of those who heard B & F organs commented on their beauty of tone. The firm did not follow early 20th century fashion by adopting large scales and high pressures. Their diapason choruses and flutes have a clear singing quality; reed tone was full of character but not aggressive. Unfortunately, when action failed, builders were faced with work of major construction rather than with overhaul. In many instances it was considered simpler to replace rather than rebuild an instrument. Pipework, even when retained, often suffered from the bubble-and-squeak excesses of the later 20th century |

Very few of his organs survive in original condition in Britain; though at least one has been converted to electric action with the transformers retained. The firm exported a number of organs, principally to the South Pacific and South Africa - their magnum opus (IV/P 62) is at Pietermaritz Town Hall (for picture see here ).

At least eight went to Australia, including one for Brisbane Catholic cathedral. The firm seems to have employed a modified action on organs intended for overseas. Perhaps there were doubts about the ability of the delicate metachotic system to survive travel.

Two Brindley and Foster instruments arrived in New Zealand and retain their original pipework unaltered. It is hoped that these will be described in following pages by people who know them well.

At least eight went to Australia, including one for Brisbane Catholic cathedral. The firm seems to have employed a modified action on organs intended for overseas. Perhaps there were doubts about the ability of the delicate metachotic system to survive travel.

Two Brindley and Foster instruments arrived in New Zealand and retain their original pipework unaltered. It is hoped that these will be described in following pages by people who know them well.

David Bridgeman-Sutton,

May, 2008

May, 2008

Thanks to the following for the use of pictures:-

1 – John Norman;

2 & 3 - Edward Bennett of Goetze & Gwynne;

1 – John Norman;

2 & 3 - Edward Bennett of Goetze & Gwynne;