They might sound like a breakfast cereal, but Booth's Puffs were a revolutionary concept for ensuring constant wind supply. But where are they now? David Bridgeman-Sutton investigates.

Booth's Puffs

|

Joseph Booth (1769-1832) was an organ-builder in Wakefield, Yorkshire. He was apprenticed into a world of modestly-sized instruments, usually of GGG manual compass and without pedals. He lived to build some of the large organs that came into fashion in England in the first third of the 19th century.

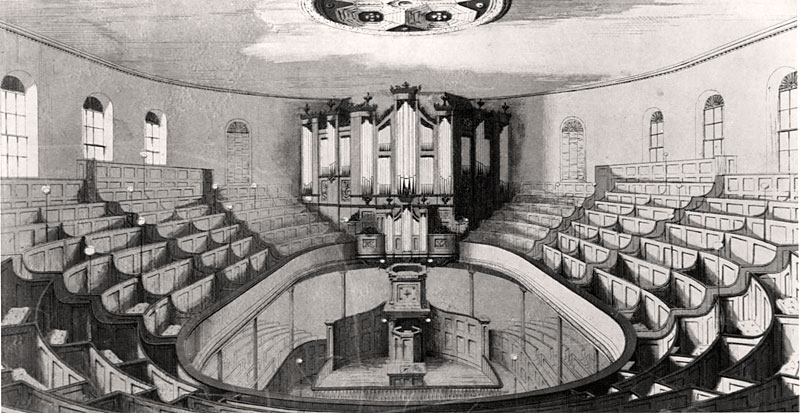

The Brunswick Chapel, Leeds, of 1827, is shown with its Booth organ in a contemporary engraving (figure 1). |

The Georgian cases of Booth's youth clearly influenced exterior design. Its size meant that display pipes in the numerous compartments were often a considerable distance from their parent wind-chest. This introduced problems: connection via long runs of tubing would have affected speech. Even with very large diameter tubes, necessary to avoid an overall drop in pressure, promptness and articulation would have been spoiled.

Carey Moore points out another difficulty. Large pipes fed by direct conveyancing from the chest tend to rob others of wind and "any repetition in playing these pipes [can result] in unsteady wind in other pipes sounding on the same chest". In the 1960s, an octogenarian organ-builder who had known the Brunswick instrument before the drastic rebuild of 1903 recalled that some large interior pipes were also "stood off" on separate chests.

These independent chests needed connection to the main action. Additional tracker work could have been incorporated, but at great complexity, cost and additional key-resistance. To operate these chests, Booth developed the first form of pneumatic action, retaining mechanical action elsewhere. His "puffs" won him a place in musical history, though none remain.

Carey Moore points out another difficulty. Large pipes fed by direct conveyancing from the chest tend to rob others of wind and "any repetition in playing these pipes [can result] in unsteady wind in other pipes sounding on the same chest". In the 1960s, an octogenarian organ-builder who had known the Brunswick instrument before the drastic rebuild of 1903 recalled that some large interior pipes were also "stood off" on separate chests.

These independent chests needed connection to the main action. Additional tracker work could have been incorporated, but at great complexity, cost and additional key-resistance. To operate these chests, Booth developed the first form of pneumatic action, retaining mechanical action elsewhere. His "puffs" won him a place in musical history, though none remain.

|

Carey Moore has illustrated a form of action used in the organ at Great Ellingham Methodist church in Norfolk (picture 2). Applied to a pedal rank and to display pipes, its working closely resembles that of Booth's puffs as described by earlier writers.

When a key is depressed, the pipe hole on the main wind chest supplies wind to the small bellows, or motor, on the independent chest, via a tube c. 5/16" (8 mm) outside diameter. The motor inflates, raising the wire on which are mounted two discs. The lower of these shuts off the pipe from the atmosphere as the upper admits wind. |

|

When the key is released, the motor collapses, the upper disc drops and shuts off the wind to the pipe, while the lower, also dropping, allows pressure to the pipe to fall off quickly. With proper adjustment, response is virtually instantaneous and any unsteadiness caused to pressure in the main wind-chest is averted.

Note that the motors at Great Ellingham are of traditional wedge-shaped bellows shape. Carey suggests Booth used these rather than circular suggested by earlier writers, who may have been misled by the discs. Certainly, there would have been no advantage in Booth deserting a form familiar for centuries in his trade. One who might have thrown much light on unresolved questions was Joseph Booth's descendant (great- great- granddaughter?), Dr Constance Tipper (picture 3). Her own professional life is an epic in itself and well-worth a visit. She was also a keen organist, who well into old age ~ she lived to be 101 ~ played every Sunday at a Lakeland village church. It was there that by chance I met her. She was inside the instrument at the time, adjusting a fault. Her knowledge of the family firm and its work was considerable, not withstanding that it had closed many years before her birth. If only I had asked her about Leeds and the puffs . . . |

David Bridgeman-Sutton,

May 1, 2004

May 1, 2004

Picture captions/credits:

Thanks for permission to use pictures to:

No 1 - Leeds City Library: www.leodis.net

No 2 - Carey Moore ~ to whom thanks are also due for much technical information.

No 3 - The Principal and Fellows of Newnham College, Cambridge

Thanks for permission to use pictures to:

No 1 - Leeds City Library: www.leodis.net

No 2 - Carey Moore ~ to whom thanks are also due for much technical information.

No 3 - The Principal and Fellows of Newnham College, Cambridge