The pleasure of organ playing was spoiled for the Victorian E.J. Hopkins* by the knowledge that it could only be achieved by "the toil and exhaustion of fellow-beings" who operated the bellows. Those who shared this view seem to have been greatly outnumbered by those whose pleasure was ruined by the cost, unreliability (and thirst!) of human organ-blowers. Attempts to replace people with mechanical devices go back to the early history of the instrument. Scanty records often suffer from the confusion that attends the description of scientific matters by the technologically unversed. The fact that many such descriptions exist only at second- or third- hand in corrupt translations does nothing to help, as is illustrated by the hydraulus or water-organ.

Two thousand years ago, both Marcus Vetruvius Pollio, the Roman architect and Hero, the Greek mathematician, wrote independently about this instrument; then knowledge of both instrument and writings disappeared during the Dark Ages. When Renaissance scholars attempted to interpret fragments of these descriptions, widely differing interpretation were put on them.

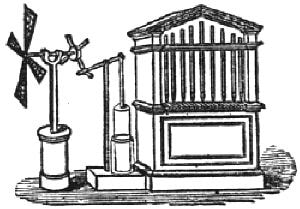

One school of thought was that an organ blown by water-power had existed, another that sound had somehow been produced by forcing water through organ pipes and a third that a theoretical but impractical machine was described. The discovery in the 1880s of a clay model at Carthage and of the remains of a hydraulus near Budapest half a century later confirmed views of an instrument, manually blown with something resembling a huge bicycle pump, and having a wind-reservoir that floated on water to equalise pressure.

One school of thought was that an organ blown by water-power had existed, another that sound had somehow been produced by forcing water through organ pipes and a third that a theoretical but impractical machine was described. The discovery in the 1880s of a clay model at Carthage and of the remains of a hydraulus near Budapest half a century later confirmed views of an instrument, manually blown with something resembling a huge bicycle pump, and having a wind-reservoir that floated on water to equalise pressure.

|

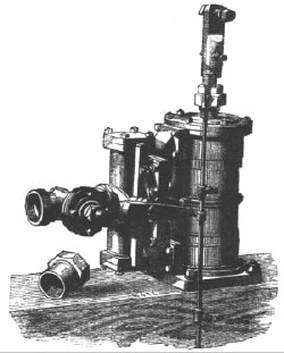

About the same time, a young ~ and remarkably cheerful and enthusiastic ~ railway engineer, David Joy, was asked to hand-pump an instrument in the house of a relative. This led him to invent the hydraulic-engine. As can be seen in figure 2, the railway parentage is apparent. A piston within the cylinder rises and falls as water pressure is applied alternately below and above. This movement is transferred to the bellows handle, the supply of water being shut off by a valve when the reservoir is full. This simple and largely trouble-free device was widely used wherever adequate water supplies existed.

|

Even where they have been replaced by electric blowers, engines are sometimes kept as museum pieces. One can ~ or could recently ~ be seen in the vestry of the Anglican church at Port Chalmers in New Zealand's South island, another as far away as Clumber church, in England's Dukeries, Nottinghamshire. There are many, geographically, in between ~ some still working.

Figure 3 shows more Victorian technology pressed into the service of organ-blowing. The house is a manor in Wales where a hydraulic ram was used to lift water to a cistern ~ represented by a rectangle in the trees ~ from a stream. This water, fed to the house, supplied both domestic needs and that of the Joy engine attached to the music room organ.

Rams were entirely automatic, using the force of flowing water to raise often considerable quantities to higher levels. Like the Joy engine, they were reliable and cheap to maintain and they needed no external source of power. This was organ blowing at virtually no cost, with no hints at the end that a spot of beer, paid for by the organist, would be welcome .

Rams were entirely automatic, using the force of flowing water to raise often considerable quantities to higher levels. Like the Joy engine, they were reliable and cheap to maintain and they needed no external source of power. This was organ blowing at virtually no cost, with no hints at the end that a spot of beer, paid for by the organist, would be welcome .

David Bridgeman-Sutton,

September 2002

September 2002

The story of organ blowers, part III, concluding:

*E.J. Hopkins: with E.F. Rimbault author of the monumental The Organ: Its History and Construction (1855 and 1877). Reprinted Bardon Enterprises 2000.