Automobile blues

So you think you're encumbered with your volumes of Bach, Buxtehude and hymnal, complete with organ shoes, gown, and peppermints when you go to the organ? Thank your lucky stars you don't also have to travel with the paraphernalia needed by a motorist 100 years ago, as David Bridgeman-Sutton muses.

|

What’s in your car tool-kit?

A century ago, motoring journalists – the first of their kind – urged every driver to carry a mallet, a cold chisel, leather belting, vulcanising kit and tyre-levers, a “densitometer” and enough nuts, bolts and washers to stock a small hardware shop. A vehicle-owner who did not employ a full-time mechanic was regarded as eccentric, if not actually deranged. Everywhere the motor went, the mechanic went too ~ “on” the vehicle rather than in it, as the then-current phrase went. Picture 1 shows why.

|

Expert help was needed constantly. Electric? steam? petrol? The choice had to be made and each form of propulsion had its advocates. Electric vehicles were quiet and comparatively easy to drive, but their short range between battery recharges limited their appeal. Steam vehicles had similar virtues; but they also had boilers. Explosions in ships and factories had given these a fearful reputation. Matters weren’t helped when some manufactures decided that the best place for this part of the machinery was under the seats! Many “steamers” have lasted to become veterans, and at least one elderly farmer in the 1960s rated his White of thirty years before as the best car he’d ever driven. Most people went for petrol engines.

|

John Betjeman records in a poem how an entire London street was aroused from sleep by an early Delauney-Belleville (left) ascending a hill in reverse (lowest) gear. The importance of hill-climbing was illustrated by one of those early journalists who invited readers to compare the performance of two cars covering the same two mile stretch. The first mile was uphill, the second downhill.

“If the first car . . . mounts the hill at four mph and descends at 30 mph, its average speed in spite of illegal and breakneck speed downhill, would only be a shade over seven mph. If the other car ascends at 10mph and descends at 30mph, its average will be 15mph. At the end, the second car would be nine minutes ahead of the first”. |

|

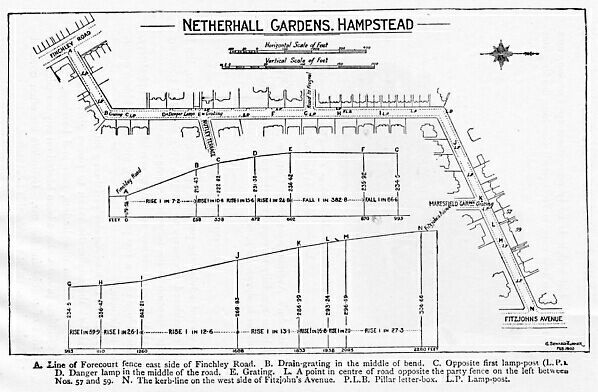

An aid to assessing performance was given in the form of a map and contour of a suggested test area (pic 2) The map was, surely, the most detailed ever provided for motoring, with every lamp-post, drain-cover, fence and pillar box marked. At four – or even 10 – mph, drivers had plenty of time to savour these delights. What residents of Netherhall Gardens thought of it all isn’t recorded.

|

|

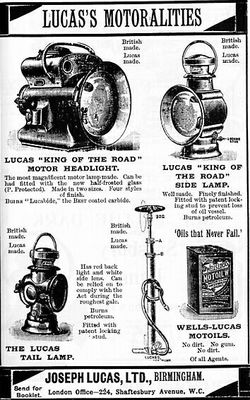

Even when a vehicle was chosen, decisions didn’t end. Items regarded as standard to-day, such as lights, horns and even windscreens, were treated as accessories. (Someone tried to introduce the term “Motoralities” for these: mercifully, they weren’t successful – see picture 3.) Acetylene, oil or electric lighting? Horn, whistle, gong or bell? The novice motorist – and most were novices a century ago – learned by trial and, frequently, by error. The worst error was to buy from an "agent" who wasn’t an agent at all. Despite editorial warnings and full-page advertisements by manufacturers, dozens of would-be buyers parted with cash to these con-artists.

Most organists were too sensible – or too hard up – to become involved: they used public transport. |

David Bridgeman-Sutton,

February 2, 2006

February 2, 2006