It would be interesting and instructive – were the raw data available – to compile a league table of monuments ranked by the callings and avocations of those remembered. Military leaders and politicians would probably tie for first place.

|

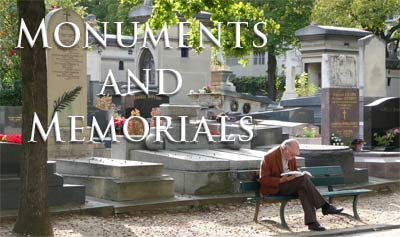

Applying the reasoning of Dr Herbert Ellis*, undertakers might well be those least represented, quite possibly with a nil score. Somewhere between these two extremes – perhaps two-thirds of the way down – we should find musicians. Henry Purcell's (1659 - 1695 ) memorial (picture 1) is in Westminster Abbey, where he was appointed organist in 1679, after having tuned the instrument for several years.

The wording is curious in stating that he is gone "to that Blessed Place where only his harmony can be exceeded." The misrelated adjective could make the words seem less than complimentary! His early death is regarded as a great loss to music generally, and to English music in particular; in fact, his family came from Tipperary, in Ireland. George Frederick Handel (1685 – 1759) also has a monument in the Abbey – a very fine life-sized statue of the composer, surrounded by various musical instruments and with the score of Messiah. This was by the outstanding French sculptor Louis-François Roubillac, who was Handel's younger contemporary. |

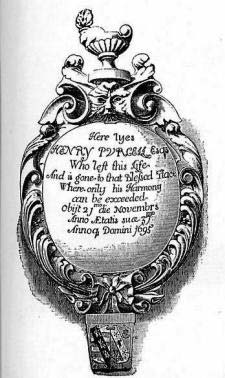

Less well-known to the English-speaking world, perhaps, is the statue at Paris Opera House (picture 2 - click on the image to get fuller detail). The spelling used here, Haendel, is general in Europe and was one of four variants used by George Frederick himself. It is as well for him that he didn't live in the age of bankers' cards, credit agencies and income tax.

Its companion piece is of Jean-Baptiste Lulli (1632 – 1687), an Italian composer who adopted both French citizenship and the French style in writing scores for ballet, the opera and incidental music for the theatre. His popularity at the Court of King Louis XIV enabled him to survive a scandalous private life that would have ruined most people. All the King's doctors could not save him, however, when he injured his foot, striking it when beating time on the floor with a wooden staff, as was the custom at that time. The wound turned gangrenous and he died, the end hastened by his own stubbornness.

|

A once well-known Paris monument is the unusual gravestone (pic 3) of César Franck (1822 – 1890). Organ professor at the Conservatoire, he was a popular and effective teacher with the reputation of being a cheerful saint. Perhaps that is why the angel hovers above. The organ at which he is shown seated is that of St Clotilde, where he was titulaire for more than 30 years; large congregations attended to hear him extemporise. His death, like that of Lulli, was the result of an accident. A horse-drawn tram struck the carriage in which he was riding. Resulting weakness left him unable to throw off a cold and he succumbed to pneumonia.

|

|

The St Clotilde instrument was by Aristide Cavaillé-Coll (1811–1899), who may be the only organ-builder to have a public square named after him (pic 4) - an honour he richly deserved.

Perhaps, with new suburbs and cities needed to accommodate a growing world population, the idea may be more widely taken up. Fisk Freeway may lead to Rieger Rise; having passed Casavant Close and Willis Way, the traveller could come to a block of flats, Marcussen Mansions. Only the longest thoroughfare would have room for the nameplates of South Island Organ Company Street. |

David Bridgeman-Sutton, May, 2011

* see Herbert Ellis MD: Why Not Live A Little Longer (ISBN 1 86106 657 0).

Picture credits: Thanks to Timothy Shaw (1) Jenny Setchell (2) Philip Wells (3 and 4).