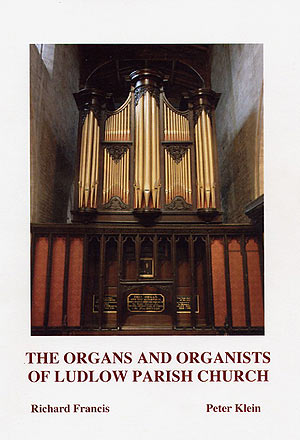

The Organs and Organists of Ludlow Parish Churchby Richard Francis & Peter Klein

Little is known of Ludlow instruments before the Snetzler of 1764. The case and many pipes of this 3 manual (no pedal) organ of 19 speaking stops remain. The form the organ takes today stems largely from extensive reworking and enlargements by Gray & Davison from 1860 onward.

Later work by Hill, Walker and most recently by Nicholsons results in a four-manual organ of 53 speaking stops. Although there have been losses — Snetzler’s dulciana among them — each builder has tended to conserve and add to what he found. The result is a versatile and very English organ that owes its survival to a cautious and considered approach to change.

|

If Ludlow had been caught up in the Industrial revolution that altered other West Midland towns beyond recognition things might have been very different; a Henry Willis or a Robert Hope-Jones would, in all probability, have refashioned the organ into his own style.

Richard Francis, who recently retired as organist of the church, presents a very detailed picture of each builder’s contribution, of when and how changes were made and in most recent cases of the thinking behind these. It is a very readable general history illustrated both pictorially and with considerable technical detail. Many insights are given into the problems faced by those who have care of organs; some, including those caused by the use of a material called “tosh” were new to your reviewer.

The succession of Ludlow organists is traced back to about 1470 by Peter Klein. Over 50 names are listed with dates (these latter are, in some cases, tentative) and there may have been others of whom no record has been left. Biographical notes reveal a rich assortment of characters, many highly-qualified some of whom went on to cathedrals. They also show something of small-town politics, especially in the days when organists were appointed by municipalities rather than by Church Councils.

This is a most interesting historical account: a great advantage is that its subject is there to be seen, heard and enjoyed.

Richard Francis, who recently retired as organist of the church, presents a very detailed picture of each builder’s contribution, of when and how changes were made and in most recent cases of the thinking behind these. It is a very readable general history illustrated both pictorially and with considerable technical detail. Many insights are given into the problems faced by those who have care of organs; some, including those caused by the use of a material called “tosh” were new to your reviewer.

The succession of Ludlow organists is traced back to about 1470 by Peter Klein. Over 50 names are listed with dates (these latter are, in some cases, tentative) and there may have been others of whom no record has been left. Biographical notes reveal a rich assortment of characters, many highly-qualified some of whom went on to cathedrals. They also show something of small-town politics, especially in the days when organists were appointed by municipalities rather than by Church Councils.

This is a most interesting historical account: a great advantage is that its subject is there to be seen, heard and enjoyed.

Reviewed by David Bridgeman-Sutton, May, 2007