Buttoning up

What's the story behind those cute little buttons found on (almost) every pipe organ?

DAVID BRIDGEMAN-SUTTON follows the development of the organist's best friend

DAVID BRIDGEMAN-SUTTON follows the development of the organist's best friend

|

Forty-two brass discs proved to be a landmark in organ playing. These were the world’s first thumb-pistons, placed beneath the keys of Henry Willis’s 1855 organ for St George’s Hall, Liverpool. It is not too much to say that ideas on registration were transformed overnight.

Thereafter, these substantial metal discs were to be found in most large Willis organs. |

Other builders were quick to develop their own systems, generally employing the smaller type of piston – then made of ivory – still in use. The obvious next step – to make these adjustable – was not taken until 1882. In that year, the New York builder, Hilborne Roosevelt – perhaps best remembered for his windchest – provided the first adjustable pistons on an organ he built in New England.

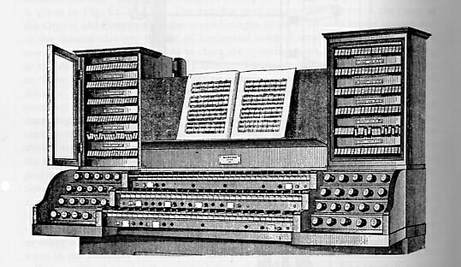

A complex and delicate mechanism was used to achieve this. Picture 1 shows the Roosevelt console layout, with stops in stepped tiers beside the manuals and the switching mechanism in cabinets either side of the music desk. Audsley remarks that the glass fronts to the cabinets protected the switches “from dust and interfering fingers” How quickly those fingers appeared on the scene!

A complex and delicate mechanism was used to achieve this. Picture 1 shows the Roosevelt console layout, with stops in stepped tiers beside the manuals and the switching mechanism in cabinets either side of the music desk. Audsley remarks that the glass fronts to the cabinets protected the switches “from dust and interfering fingers” How quickly those fingers appeared on the scene!

|

Ten years later, Willis introduced his first adjustable pistons at Hereford cathedral, complaining that the work “nearly killed” him! He was persuaded to undertake this by the cathedral organist, G.R. Sinclair, who was a friend of Edward Elgar, and the subject of one of the Enigma variations. (Some authorities claim that Sinclair’s bulldog Dan was the real subject). An unusual portrait in enamels is to be seen on GRS’s monument in the south aisle of the cathedral.

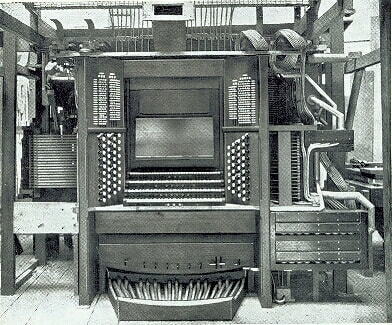

In the Willis system, adjustment was made by means of small setter pistons placed above the stop-knobs. These can be seen in Picture 2, a photograph of the organ during construction. The presence of “traces”, or square-section wooden rods, shows that the draw-stop action was at least partly mechanical. |

|

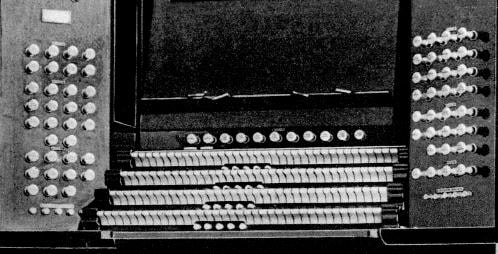

Console features often enable the builder, and even the approximate date of an instrument, to be identified at a glance. Hill used a number of distinctive piston types over the years. The earliest version is that on the Sydney Town Hall organ – a rather chunky disc of solid ivory. This style was modified (c. 1890 – 1920) when the firm adopted a new pattern for manual keys. These overhung the key slips to a considerable depth. To accommodate pistons, which had to be made longer than usual, a rectangular “slice” with quadrant corners, had to be cut in the overhang. These features are seen, from slightly different angles, in picture 3 (Ulster Hall, Belfast 1903 rebuild) and picture 4 (All Hallows, Gospel Oak 1915).

|

|

Round pistons can have their drawbacks. They, or the numbered labels in the heads, tend to rotate slightly. To a hypercritical eye, this results in an untidy console. John Norman, former managing Director of Hill, Norman and Beard explains his company’s later change of design. A cathedral organist, irritated by real or imagined irregularities in this respect, would occupy himself in sermon time by “correcting” irregularities. The result was, not infrequently, a broken piston and an anguished cry for immediate help. Square pistons, possibly suggested by the juke-box, were therefore introduced. A console so equipped is to be seen at Beverley Minster.

|

|

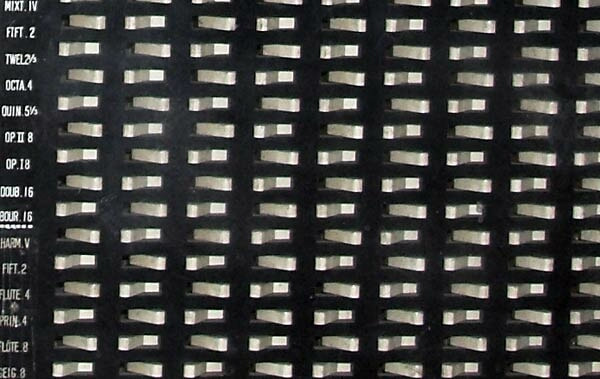

Adjustment by switchboard – as used by Audsley – or individual setters for each piston – as used by Willis – resulted in vast and complex arrangements in large organs. Picture 5 shows the setter board for only part of the Great in the organ of Norwich cathedral. The whole board covers a considerable area.

The single setter piston, which captures any combination to any piston was made practical by solid state circuitry, though there had been complicated systems earlier. In the words of the (very) old joke, this enables the organist to change his combinations without leaving his seat. |

|

The Fisk organ in All Saints’ Church, Ashmont, Boston, USA (Picture 6) although far from one of the firm’s largest, has a wealth of pistons, both manual and pedal with adjustment by setter piston. The console must be a magnet to organists. One wonders if successors to the “interfering fingers” that so annoyed Audsley ever get to work.

|

David Bridgeman-Sutton,

November 12, 2005

November 12, 2005

Sources , acknowledged with thanks:

- Picture 1- Audsley Art of Organ Building:

- Pictures 2 and 4 - The Laycock archive:

- Picture 3 – John Norman;

- Picture 5 – Jenny Setchell;

- Picture 6 - Mark Nelson at C.B. Fisk.