Facing the Music

Pic 1. Kilpek church corbels (Click to enlarge)

Pic 1. Kilpek church corbels (Click to enlarge)

Representations of the human head are among the most familiar forms of architectural decoration.

Approximately globular, they are ideal as a corbel - the brackets that support an arches, beams and other overhanging structures. In great churches and abbeys, where saints, kings, queens, abbots and abbesses have been portrayed, it is usually as noble, devout and virtuous. No craftsman wanted to offend patrons or others of the powerful with painful honesty.

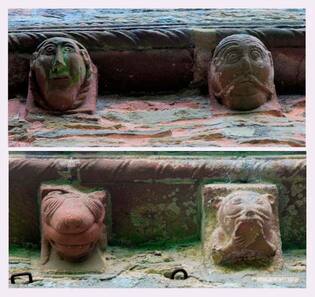

In more remote districts, where the models were the ordinary folk of the neighbourhood and sometimes the mason's fellow workers greater honesty prevailed. People were either portrayed as nearly as possible as the carver saw them, or with exaggerated quirks and peculiarities. Sometimes, caricatures were kindly, affectionate even; sometimes they were a means of settling old scores. Picture 1 is a montage of photographs by Gerry Cordon of corbels at the church of Kilpeck, near the border between England and Wales. The first of the top pair is a strong-minded looking woman, her hair is thickly plaited, her face is lined with pain or worry. The second is an elderly man, his flowing moustache carefully tended, who has an air of self importance; perhaps he is a former soldier used to command. It is not hard to imagine him expressing forceful opinions in the village inn.

The lower pair is enigmatic - is it a pig and a dormouse? Perhaps, but they seem to have human characteristics and could well represent villagers who were notably greedy or timid. Their contemporaries would have recognised them; after 900 years it is unlikely that we shall ever know their history. A slide show of the figures, human, animal and mythical, that adorn the church is found here.

Approximately globular, they are ideal as a corbel - the brackets that support an arches, beams and other overhanging structures. In great churches and abbeys, where saints, kings, queens, abbots and abbesses have been portrayed, it is usually as noble, devout and virtuous. No craftsman wanted to offend patrons or others of the powerful with painful honesty.

In more remote districts, where the models were the ordinary folk of the neighbourhood and sometimes the mason's fellow workers greater honesty prevailed. People were either portrayed as nearly as possible as the carver saw them, or with exaggerated quirks and peculiarities. Sometimes, caricatures were kindly, affectionate even; sometimes they were a means of settling old scores. Picture 1 is a montage of photographs by Gerry Cordon of corbels at the church of Kilpeck, near the border between England and Wales. The first of the top pair is a strong-minded looking woman, her hair is thickly plaited, her face is lined with pain or worry. The second is an elderly man, his flowing moustache carefully tended, who has an air of self importance; perhaps he is a former soldier used to command. It is not hard to imagine him expressing forceful opinions in the village inn.

The lower pair is enigmatic - is it a pig and a dormouse? Perhaps, but they seem to have human characteristics and could well represent villagers who were notably greedy or timid. Their contemporaries would have recognised them; after 900 years it is unlikely that we shall ever know their history. A slide show of the figures, human, animal and mythical, that adorn the church is found here.

Pic 2. Bourges (Click to enlarge)

Pic 2. Bourges (Click to enlarge)

From neat moustaches to the wild and straggling kind. The organ case at Bourges, in central France, is of markedly rustic workmanship and has an unusual - possibly unique - pipeshade in the central tower, the flowing moustache of . . . whom? (Picture 2).

The face is a mask that could be categorised as a grotesque, but it seems to represent a real person, again one with an air of self-importance - and also of ill-temper? Perhaps he was an official of the town, a 17th century equivalent of a traffic warden who had given the organ builder a ticket for parking his barrow on a double-yellow line.

The face is a mask that could be categorised as a grotesque, but it seems to represent a real person, again one with an air of self-importance - and also of ill-temper? Perhaps he was an official of the town, a 17th century equivalent of a traffic warden who had given the organ builder a ticket for parking his barrow on a double-yellow line.

|

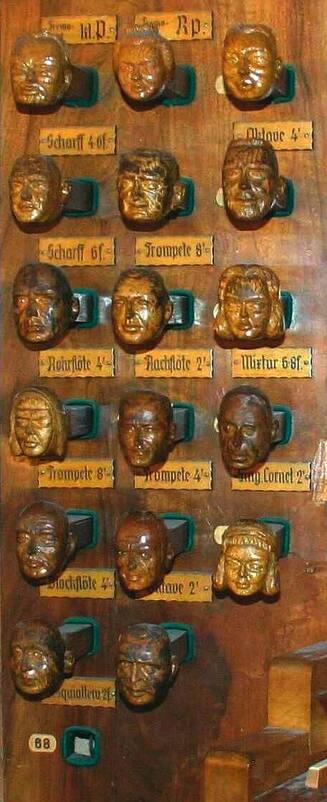

Faces that are portraits, not caricatures, are found as stop-heads on a disused organ console at St Jacob's Hamburg. Picture 3 shows one of the four banks of these.

Luminaries - many long-extinguished - of the city's musical and civic worlds are portrayed. JS Bach, who more than once walked to Hamburg, appears in the middle of the right hand column. Johann Adam Reinken, organist of St Jacob's, whose playing Bach was anxious to hear, is also represented, together with his predecessor and teacher. Heinrich Scheidermann was an influential figure in his day and has been called a founding father of the North German organ school. Mozart is also to be found. Heads are missing for one or two registers: perhaps they represented persons who tended to behave irrationally under pressure. The history of the organ is remarkable. The largest and perhaps most famous of Arp Schnitger's instruments, it was dismantled and stored for safe-keeping during the second world war. This was a wise move, as the church, still containing the organ case, was largely destroyed in air raids. Schnitger's organ was rebuilt in a new case in the reconstructed church, the console using these stop knobs being made in the 1950s by Emerich Kozma. Unfortunately, there were mechanical problems and another, closer to the original, was substituted. Happily Kozma's work remains to intrigue visitors. |

|

An unlikely combination occurs in the organ of Bowwood House, Wiltshire England (picture 4). This case was originally made for a private house in Mayfair, London's most fashionable district. It is of Italian walnut, elaborately carved and gilded, and with a graceful pediment on which four cherubs play on trumpets and a lyre. Within this pediment is a sunburst, at its centre a female's head of classical Greek form. She must, surely, represent one of the daughters of Zeus, father of the Gods on Mount Olympus. His seven daughters were the Muses, each of whom inspired one of the arts. This is probably intended for Euterpe, patron of music, though she might, just possibly be Polyhymnia, muse of sacred poetry and hymns. A closer view of the pediment is shown in the lower photo.

|

Finally, more heads than you can count? At Rodez cathedral in the Pyrenees, Antoine Vernoles of Poitiers built a great organ in 1629. To decorate its case, he employed Raymond Gusmond, a master sculptor from Perigueux. It is hard to estimate how long this work must have taken M. Gusmond - see picture 5 - but it is not possible to think of a more elaborate one anywhere. For a competition, Jenny Setchell invited people to count the number of heads visible in the picture. Memory suggests that the correct number was 44. The competition is long-closed - so please don't offer any revised estimates!

David Bridgeman-Sutton, January, 2011

Picture credits:

1. Gerry Cordon

2, 3 and 5: Jenny Setchell.

4: Phillip Wells

1. Gerry Cordon

2, 3 and 5: Jenny Setchell.

4: Phillip Wells